Marina Mniszech was young, beautiful, and wildly ambitious. Raised amid the lavish trappings of a Polish noble court – where money changed hands faster than common sense could catch up – Marina Mniszech was destined to become a queen. And she did. For a moment. Her story is a textbook example of how dreams of power can twist into nightmares, and how the political game of thrones often ends in death… and not just for the players.

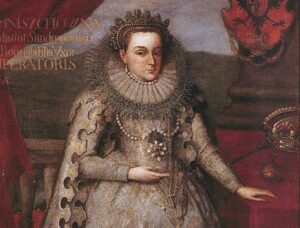

Beautiful Marina Mniszech

Marina was born in 1588 in Laszki Murowane – a small village that would have sunk into obscurity were it not for her infamous name. She was the daughter of Jerzy Mniszech, Voivode of Sandomierz and Starost of Sambor – a man more famous for his cunning and brazenness than for any particular moral standing. Mniszech had built an enormous fortune, but also a reputation for shameless manipulation. People whispered that „he always lands on his feet”, no matter the scandal. Meanwhile, he was drowning in debt. Quite literally. The kind of financial ruin that expensive dinners, gilded furniture, and vintage wines couldn’t conceal for long.

Marina grew up in a world of appearances – golden picture frames, embroidered gowns, and the constant pretence that everything was fine. She received the standard aristocratic education for noble girls: reading, writing, embroidery, singing.

Her beauty was undeniable. She had the kind of looks that turned heads at court and triggered whispered commentary behind folding fans. That allure would soon become her greatest political asset in one of the riskiest diplomatic gambles in the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Marina Mniszech and Grigory Otrepyev

In 1604, someone arrived in Sambor who – at first glance – didn’t inspire much confidence. False Dmitry – the man who claimed to be the miraculously saved Tsarevich Dmitry, son of Ivan the Terrible – didn’t come to the Mniszech estate by accident. He needed to win over Polish nobles to support his wild vision of marching on Moscow and seizing the Russian throne. Jerzy Mniszech, neck-deep in debt, had exactly what every pretender needed: influence, contacts… and a daughter he could put to good use.

Dmitry – really a defrocked Orthodox monk named Grigory Otrepyev – wasn’t just audacious, he was also incredibly convincing. He spoke fluent Polish, picked up Latin, and glided effortlessly through the salons of the nobility, promising untold riches to anyone willing to help him.

His plan was clear: take Moscow by storm. In exchange for Jerzy’s support, Dmitry offered marriage to Marina and a treasure trove of land and privileges. Marina was to become Tsarina of Russia—not out of love, but out of cold calculation.

A Deal Worthy of a Royal Betrayal

On May 26, 1604 Jerzy Mniszech and Dmitry signed a contract that sounded like something straight out of a baroque political soap opera. Marina would marry Dmitry if – and only if – he secured power in Moscow.

In return, the rewards would be astronomical. Mniszech was promised the territories of Smolensk and Severia, along with a jaw-dropping one million Polish zloty. Marina would receive the duchies of Novgorod and Pskov. This deal was meant to drag the Mniszech family out of bankruptcy and lift Marina straight onto a throne.

At first, the whole thing seemed like a fantasy. But then, fate intervened. In 160, Tsar Boris Godunov died unexpectedly, throwing Russia into chaos. False Dmitry claimed the throne and was crowned Tsar in Moscow. The news swept into Poland like a storm. Everything was going according to plan.

In November that same year, Marina’s wedding was held by proxy—without the groom, but in the presence of King Sigismund III Vasa himself. The ceremony was lavish, overflowing with pearls, diamonds, and gold.

Marina’s future seemed wrapped in incense and imperial silk.

Ten Days of Glory. Coronation and Catastrophe

In the spring of 1606, Marina set out for Moscow. Her journey resembled a royal procession. Crowds greeted her with flowers and cheers as the future Tsarina of Russia. In May, she was officially crowned in the Dormition Cathedral. Marina became Tsarina—the first Polish woman ever to hold that title. She had achieved what no other noblewoman from the Commonwealth had even dared to dream.

But the fairy tale unraveled after just ten days. On the night of May 26–27 1606, the Kremlin erupted in bloodshed. A mob, incited by boyars enraged by Dmitry’s rule and the Polish presence at court, stormed the palace. Dmitry was brutally murdered.

Marina barely escaped with her life, dressed in her maid’s clothing as she fled the carnage. Her father, Jerzy, was captured. He promised bribes, alliances—whatever it took. None of it helped. Both he and Marina were thrown into prison.

See also: Wife of Mieszko the Old – the Mysterious Princess

A Second Pretender, a Second Chance

After two years in captivity, Marina spotted a new opportunity. Another False Dmitry emerged—Dmitry II—who, despite being even less credible than the first, also claimed to be the miraculously spared Tsarevich. Marina didn’t hesitate. She dove back into the same treacherous waters. Once again, she played the part of the Tsar’s consort, even though there was no formal wedding this time around.

In Tushino, where Dmitry II set up his own “court”, Marina assumed the role of queen-in-exile. In 1610, she gave birth to a son, Ivan. The child was hailed as the new heir to the Russian throne, a symbol of uniting the ancient Rurikid line with the might of the Polish magnates.

But history had other plans. Dmitry II was killed, and Marina, ever the survivor, aligned herself with a Cossack leader—Ivan Zarutsky. It would be her final alliance.

See also: Anastasia – Wife of the Unfortunate Piast Prince

Together with Zarutsky, Marina attempted one last gambit: to place her son Ivan on the throne. They plotted a coup and tried to rally the Cossacks and nobility behind them. But by then, Russia had had enough of impostors and foreign intrigues.

In 1614, their escape failed. Zarutsky was executed. Young Ivan—the boy meant to rule—was hanged in public. Marina died not long after, in a prison cell. No one knows exactly when or how.

Her death was as quiet as her rise had been thunderous.

Bibliography

-Andrusiewicz A., Carowie i cesarze Rosji, Warszawa 2001.

-Andrusiewicz A., Dzieje Dymitriad 1602–1614, t. 1–2, Warszawa 1990.

-Andrusiewicz A., Dzieje wielkiej smuty, Katowice 1999.

-Andrusiewicz A., Niepokorne. Silne kobiety w Imperium Romanowów, Warszawa 2019.

-Barlett R., Historia Rosji, tłum. W. Sadkowski, Warszawa 2010.

-Czerska D., Dymitr Samozwaniec, Wrocław 2004.

-Delayoe M., Historia erotyczna Kremla. Od Iwana Groźnego do Raisy Gorbaczowej, tłum. K. Szeżyńska-Maćkowiak, Warszawa 2018.

-Gelardi J.P., Niezwykłe kobiety Romanowów. Od świetności do rewolucji, tłum. J. Wołk-Łaniewski, Warszawa 2012.

-Ochmański J., Dzieje Rosji do roku 1861, Warszawa–Poznań 1986.

Author: Gabriela Zapolska