Grzymisława was not merely the wife of Leszek the White. After his tragic death, she had to confront powerful magnates, hostile princes, and the chaos of a fractured state on her own. As regent, she fought for her son’s future, unafraid of political schemes and dramatic decisions.

The Tragic Death of Her Husband

In 1226, the only son of Leszek the White and Grzymisława was born. At his baptism, he was named after his warlike grandfather, Bolesław the Wrymouth – a sign of the far-reaching ambitions his parents held for him.

Leszek enjoyed fatherhood for only a brief time. On November 24, 1227, he invited several district princes to Gąsawa to discuss matters of state. Grzymisława, presumably, remained in Cracow, awaiting joyful news from the assembly. Instead, she was delivered a devastating message – her husband had been treacherously attacked during the meeting and killed in the most unexpected moment.

Leszek attempted to flee on horseback but was overtaken in the village of Marcinkowo, where he was brutally murdered. The masterminds of the Cracow prince’s assassination are believed to have been Świetopełk of Pomerania – the rebellious governor of Gdańsk – and Władysław Odonic of Greater Poland.

Leszek the White was buried at Wawel Cathedral on December 6, 1227, a few weeks after the attack. The funeral was attended by the dowager duchess, her infant son, and numerous secular and ecclesiastical dignitaries. According to written sources, the deceased was mourned „with immense sorrow and weeping”.

An Ambitious Regent

Following her husband’s death, Grzymisława assumed the regency during her son’s minority, with the primary goal of securing his claim to the throne. She held the title of regent officially from November 1227 until May 1228. Her authority was soon revoked, as Polish law at the time strictly prohibited women from ruling alone, leading armies, or managing unruly magnates.

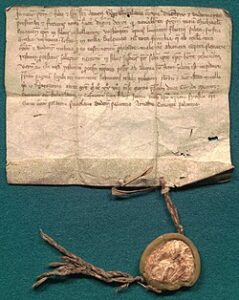

During her brief tenure, Grzymisława proved to be an enterprising and independently minded figure. She styled herself as „Ducissa Cracoviensis”, „Ducissa Poloniae” and „Ductrix Cracoviae et Sandomiriae”. She used her own seal, inscribed SIGILLVM GRIMIZLAVE, depicting a crowned woman seated on a throne, holding a scepter in her right hand. The duchess used this seal for the first time in a document issued to the Cistercians of Sulejów in early December 1227.

That same year, Grzymisława founded a Franciscan monastery in Cracow. Surviving records also indicate she supported the Benedictines in Tyniec, Sieciechów, and Łysa Góra, the Cistercians in Jędrzejów and Sulejow, the Canons Regular of Czerwińsk, and the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre in Miechów. Through numerous donations and privileges granted to churches and monasteries, she sought to win the Church hierarchy’s support for herself and her son. The clergy regarded her as deeply pious.

A Duchess with Firm Politics

Being of Ruthenian origin, it is unsurprising that Grzymisława engaged in eastern affairs. In May 1228, she met with a Romanovich whose name is not recorded in the sources. He was likely Daniel of Volhynia, who held her brother Jaroslaw captive. Historians suggest that Grzymisława, by establishing contact with the ruler of Volhynia, hoped to secure aid against the rising power of Conrad of Masovia, who was asserting his right to her son’s Cracow throne. Her motives appear purely political – she was willing to deal even with enemies if it served her goal.

Over time, the number of Grzymisława’s adversaries increased. In addition to Conrad of Masovia, claims to Cracow were also made by Wladyslaw the Spindleshanks, who had previously entered into a mutual inheritance pact with Leszek the White. In exchange for transferring the senior throne to Władysław during young Bolesław’s minority, Grzymisława demanded that the privileges of the Krakow nobility be upheld.

This arrangement was formalized at the assembly in Cień, in the Kalisz region, later in 1228. Grzymisława sent a special delegation to the meeting, including the most influential secular and ecclesiastical magnates of Lesser Poland, led by Bishop Iwo Odrowąż, Voivode Marek Gryfita, the castellan of Wislica Mszczuj, and Voivode Pakosław. In their presence, Władysław – as promised – adopted young Bolesław, acknowledged him as heir, and pledged to defend his inheritance.

However, fulfilling that promise proved too much for Władysław the Spindleshanks, who was occupied with his long-standing feud against Władysław Odonic. Grzymisława then found a new ally in Henry the Bearded, Duke of Silesia. In return for his support, she relinquished claims to the Cracow duchy and accepted a widow’s dower in the Sandomierz region, along with a promise of protection.

The Struggle for Cracow

The alliance between Grzymisława and Henry the Bearded displeased Conrad of Masovia, who decided to seize Cracow by force. Anticipating Conrad’s move, the Silesian duke prepared defensive actions in time, defeating Masovian forces at the battles of Skała, Wrocieryż, and Międzybórz in 1228.

Conrad soon retaliated. In 1229, he deceitfully captured Henry the Bearded, who had come to Spytkowice to confer with the Krakow nobility. The prisoner was taken to one of the Mazovian castles – either Płock or Czersk. Only the personal intervention of Henry’s wife, Hedwig of Andechs, a highly respected figure, secured his release.

During Henry’s imprisonment, Grzymisława also found herself in a precarious situation. Conrad of Masovia appointed his eldest son, Bolesław, as governor over her, severely restricting her movements. She was unable to form coalitions against her brother-in-law or mount any effective resistance. As if that were not enough, at the Radom assembly in 1229, Grzymisława was forced to relinquish the last piece of Leszek the White’s legacy – the Sandomierz province – which was now formally taken over by Bolesław Konradowicz.

See also: The Woman Who Killed Władysław Spindleshanks

This marked a dark and difficult chapter in Grzymisława’s life, which she had no choice but to endure. Her patience was rewarded two years later. Following the death of Władysław the Spindleshanks, Henry the Bearded launched a counteroffensive against Conrad of Masovia. His forces expelled the Masovians from Cracow. These victories culminated in a council at Sandomierz, where the widow of Leszek the White regained the Sandomierz duchy in exchange for renouncing claims to the Łęczyca-Sieradz lands in favor of Conrad.

Grzymisława’s Ordeal

Conrad of Masovia seemed unwilling to abide by the Sandomierz accords. In 1233, he committed a shameful act recorded in contemporary chronicles. Taking advantage of the turmoil in Greater Poland caused by Henry the Bearded’s conflict with Władysław Odonic, Conrad invited his sister-in-law and her seven-year-old son for a „private conversation.” Despite her distrust of Conrad, Grzymisława agreed and went to the designated location. This turned out to be a grave mistake – Conrad’s men ambushed, imprisoned, and, as one chronicler put it, “had her flogged”.

See also: Anastasia – Wife of the Unfortunate Piast Prince

Scholars interpret this term as a form of corporal punishment – possibly whipping or beating. Whatever the precise nature of the abuse, it was an extremely humiliating and traumatic experience for Grzymisława. Never before or after did she suffer such treatment. The event casts a harsh light on Conrad, who bore responsibility for his subordinates’ actions.

Following their arrest, Grzymisława and Bolesław the Chaste were taken to a monastery in Sieciechów. Their conditions and the duration of their captivity remain unknown. What is known, however, is that they were eventually rescued in a daring operation led by Klemens of Ruszcza from the Gryfita clan – an act for which Boleslaw would later express deep gratitude.

Fearing renewed pursuit from the enraged Conrad, Grzymisława fled not to Sandomierz, but to Silesia, where she could count on Henry the Bearded’s continued support.

Seeking Protection

Around the same time, Grzymisława appealed to the Holy See for protection. On December 23, 1233, Pope Gregory IX issued a bull to Archbishop Pełka, Bishop Wisław, and Bishop Thomas, responding favorably to the duchess’s plea for the return of her confiscated estates by Conrad of Masovia. These lands were to be handed over to Henry the Bearded and King Coloman of Hungary.

“Our daughter, the noblewoman Grzymisława, widow and Duchess of Sandomierz,” the Pope wrote, “has informed us that although the noble lord Conrad, Duke of Masovia, his sons, and certain other vassals of this duchess from the Diocese of Cracow, in your presence and that of your suffragans, swore an oath not only not to persecute her or her son Bolesław, but also to protect her estates from assault by others, they later invited her to a wicked assembly, stripped her of her belongings, inflicted grievous wounds upon her, imprisoned her, and unlawfully seized her possessions, including the money she had entrusted to a monastery”.

Conrad of Masovia ignored the Pope’s demands and the threat of excommunication for noncompliance. As a result, Grzymisława refrained from launching open conflict against her brutal brother-in-law. A return to Sandomierz would have meant all-out war with Conrad – something her most powerful protector, Henry the Bearded, wished to avoid at the time, being preoccupied with other matters.

See also: Agafia. The Woman Who Invited the Teutonic Knights to Poland?

Ultimately, the duchess accepted Henry’s invitation to reside at the fortified castle in Skała, near the Silesian border. There, she felt far safer than she ever could in Sandomierz, where Conrad’s knights might strike at any moment.

Bibliography:

-Chrzanowski M., Leszek Biały, książę krakowski i sandomierski, princeps Poloniae (ok. 1184 – 23/24 listopada 1227), Kraków 2013.

-Faron B., Święte i tygrysice. Piastówny i żony Piastów 1138–1320, Kraków 2018.

-Jasiński K., Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich, Poznań–Wrocław 2001.

-Labuda G., Zaginiona kronika z pierwszej połowy XIII wieku w Rocznikach Królestwa Polskiego Jana Długosza. Próba rekonstrukcji, Poznań 1983.

-Łodyński M., Stosunki w Sandomierskiem w latach 1234–1239. Przyczynek do dziejów Bolka Wstydliwego, „Kwartalnik Historyczny” 1911, t. 25, z. 1.

-Michalski M., Kobiety i świętość w żywotach trzynastowiecznych księżnych polskich, Poznań 2004.

-Rosik S., Wiszewski P., Wielki poczet polskich królów i książąt, Wrocław 2007.

-Samsonowicz H., Leszek Biały, [w:] Poczet królów i książąt polskich, red. A. Garlicki, Warszawa 1980.

-Semkowicz A., Zbrodnia gąsawska, „Ateneum. Pismo Naukowe i Literackie” 1886, t. 3.

-Sobociński W., Historia rządów opiekuńczych w Polsce, „Czasopismo Prawno-Historyczne” 1949, t. 2.

S-pórna M., Grzymisława, [w:] Słownik władców Polski i pretendentów do tronu polskiego, Kraków 2003.

-Teterycz-Puzio A., Zamachy na Piastów, Poznań 2019.

-Włodarski B., Polska i Ruś 1194–1340, Warszawa 1966.

-Zabłocki W., Grzymisława Ingwarówna, księżna krakowsko-sandomierska, Kraków 2012.

Author: Mariusz Samp